Cybersecurity is becoming an increasingly important focus for organizations, and the COVID-19 pandemic has only accentuated cyberrisk for every type of enterprise through telecommuting, the expansion of work environments with videoconferencing software, and the addition of personal devices and private WiFi networks to an organization’s systems.1 In 2022, cybersecurity has topped the list as a critical risk in the European Confederation of Institutes of Internal Auditing’s (ECIIA’s) 2022 Risk in Focus report2 and The Institute of Internal Auditor’s (IIA’s) OnRisk 2022 report3 for the fifth time. One of the most comprehensive risk studies from the World Economic Forum has also recognized cybersecurity as a top risk for several years.4 Strikingly, the OnRisk 2022 report notes that the most significant gap in internal audit competencies is related to cybersecurity. This led to an investigation into how effectively internal auditors can provide assurance about cybersecurity risk management.5

A quiz can be used to score cybersecurity audit effectiveness. Enterprises can then use the results to compare their cyberaudit effectiveness scores with an entire sample, region or industry. A proposed quiz has been developed and its effectiveness is analyzed herein based on pilot results.

What Does It Take to Get a Perfect Score?

Every internal audit has three interdependent phases: planning, performing the engagement and reporting findings.

The quiz provides a subscore for each of three phases to show which areas need improvement (figure 1). If an enterprise performs well in all three phases, its score could approach 100 (a perfect score). Scores depend on several factors, such as the enterprise’s risk appetite and exposure. The higher the score, the more the internal audit contributes to the maturity of cybersecurity risk management.

The quiz provides a subscore for each of three phases to show which areas need improvement (figure 1). If an enterprise performs well in all three phases, its score could approach 100 (a perfect score). Scores depend on several factors, such as the enterprise’s risk appetite and exposure. The higher the score, the more the internal audit contributes to the maturity of cybersecurity risk management.

Planning

The planning phase has three major steps that an internal auditor must consider:

- Creating strategic plans and understanding stakeholders’ expectations—Here the internal auditor needs to analyze industry trends in cybersecurity risk management, identify and communicate emerging cybersecurity risk to top management, and engage in a forward-looking discussion of cybersecurity threats and risk with management and the board or the audit committee to understand their expectations. However, this step is frequently ignored by auditors.6

- Making an initial risk assessment—This step directs the cybersecurity audit engagement. It includes identifying the enterprise’s most valuable digital assets (the crown jewels) and the levels of protection they warrant based on their value to the enterprise. The auditor should assess the vulnerability of identified key digital assets and the likely impact if these digital assets are stolen or compromised. All this can be done in cooperation with the first and second lines (of defense)7 in cyberrisk management: the IT team and chief information officer (CIO) or a similar function.8

- Defining audit criteria—This step defines the criteria against which internal auditors audit. If the enterprise uses international standards for mapping and measuring cybersecurity risk management processes, such as International Organization for Standardization (ISO)/ International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) standard ISO/IEC 27001 Information Security Management, COBIT®, and US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) standards, they represent the audit criteria. Other options include the Center for Internet Security (CIS) Top 20, US Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC) Cybersecurity Assessment Tool and the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO) Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) for Cybersecurity framework, and self-developed standards. Using such standards is advisable because they are developed in several iterations by professional associations and numerous experts.

Performing the Engagement

During the performing-the-engagement phase, auditors review internal controls. The first step is to define the areas of assurance activities and test internal controls put in place by the first two lines to manage cyberrisk. The quiz uses 12 areas proposed by the Association of Healthcare Internal Auditors (AHIA) and Deloitte.9 These 12 areas are:

- Cyberrisk management

- Software security

- Data protection

- Cloud security

- Identity and access management

- Third-party management

- Infrastructure security

- Workforce management

- Threat and vulnerability management

- Monitoring

- Crisis management

- Enterprise resilience

- Including business continuity planning

To check how well auditors audit these areas, the quiz adopted the logic of the International Standard on Auditing (ISA) 500 Audit Evidence, under which reperformance of controls provides the highest level of assurance, and inquiry―that is, interviewing the managers involved―the lowest level of assurance. A combination of methods (inquiry, observation, inspection and analytical procedures) ensures a better score. If the internal audit function uses reperformance as the standard, that guarantees the highest score in that part of the quiz.

The second step is to check the cybersecurity tools an enterprise uses and determine how well they perform. These tools can be network security monitoring tools, encryption tools, web vulnerability scanning tools, network defense wireless tools, packet sniffers, antivirus software, firewalls, public key infrastructure (PKI) services, social engineering tools, managed detection services, penetration testing, intrusion detection systems and endpoint protection.10 The more tools that auditors checked, the higher the quiz score.

Because of rapid changes in environments and enterprises, it is also important to consider how often findings related to cybersecurity risk management are reported to senior management and the BoD.

Reporting

Reporting

Reporting the findings to the auditees and the board of directors (BoD) is the last phase of an effective cyberaudit. Although the leave-it-to-IT logic still prevails in many boardrooms, the BoD is ultimately accountable for overseeing cybersecurity risk, and auditors can significantly help the BoD exercise its oversight. The auditors’ report to the BoD should be accurate, objective, constructive, complete and timely (International Professional Practices Framework [IPPF] Standard 2420 Quality of Communications11). This can be achieved by issuing an overall opinion about cybersecurity risk management that gives the BoD a reasonable assurance of the effectiveness of such management. Because of rapid changes in environments and enterprises, it is also important to consider how often findings related to cybersecurity risk management are reported to senior management and the BoD. The provision of an overall opinion and a higher reporting frequency led to a higher score on the quiz.

International Sample Findings

The quiz was distributed among the members of 19 IIA affiliates, three ISACA® chapters in Europe and one ISACA chapter in the United States via monthly newsletters and emails. One hundred eighty-three participants completed it, and the scores were analyzed. The demographics reveal a significant polarization of competencies. Although almost half (48 percent) of the respondents have the Certified Information Systems Auditor® (CISA®) certification or multiple certifications related to cybersecurity and IT, 40 percent of the participating internal audit functions (IAFs) have no auditors with professional certification (figure 2), 31 percent of auditors have no experience performing cybersecurity audits and 41 percent of IAFs have no IT auditors. To make up for the lack of in-house skills and to obtain reliable benchmarks, 20 percent of participants fully outsource cybersecurity audits and 65 percent cosource audits with external providers.

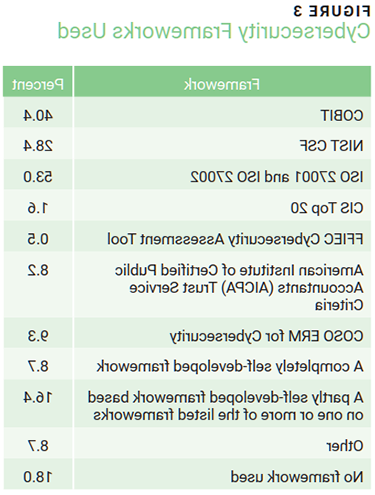

Almost one-third of the respondents come from the financial sector, one of the most highly regulated sectors for risk management in general and for cybersecurity risk management in particular. Eighty-two percent of respondents indicated that their enterprises use one or more cybersecurity frameworks in developing cybersecurity audit plans. Predominantly, they rely on ISO 27001 and ISO 27002 (53 percent), COBIT (40 percent), or NIST (28 percent). Some enterprises (16 percent) use partly self-developed frameworks that are based on these three frameworks (figure 3). Most auditors (62 percent) assessed their enterprise’s maturity level as moderate (3).

The respondents achieved a mean score of 57.9; however, the variation was high. As many as 51 percent of respondents scored higher than 61, indicating a high audit effectiveness level. Looking at the individual phases, the planning phase had the highest mean score (64), followed by the reporting and the performing phases with means of 55 and 54, respectively. However, the results showed that neither the planning and reporting phases nor the performing and reporting phases were strongly correlated. This suggests that even those auditors who do not perform the planning or performing phases effectively still provide the board with an overall opinion about risk management.

There are considerable differences between regions and sectors. Not surprisingly, the IT and telecommunications and financial sectors have the highest scores, with IT and telecommunications ranking significantly higher (75) than any other sector (figure 4). Although Australia, New Zealand and Western Europe have the highest scores among regions, the differences among regions are not significant because variation within each region is large.

Inspection is the most frequently used procedure for testing cybersecurity controls, followed by inquiry and observation; analytical procedures and reperformance are not used frequently. Twenty-five percent of respondents indicated that they do not check any cybersecurity tool, and 75 percent check one or more cybersecurity tools in an audit cycle.

Forty-three percent of the IAFs report to the BoD annually, and 14 percent report their findings quarterly or at every committee meeting. Thirteen percent of respondents do not report any findings to the BoD.

Increasing Cybersecurity Audit Effectiveness

Once a score has been determined, auditors can use that score to dictate next steps for the organization to improve its cybersecurity audit processes and, thus, increase its score. There are several best practices internal auditors can follow to increase their cybersecurity audit effectiveness, including:

- Upskill—One factor that can significantly increase audit effectiveness is increasing internal auditors’ competencies by encouraging and helping them to get certified. As reported, the most popular certification in the sample is the CISA credential. Cybersecurity audits require specialized knowledge and skills that only upskilling can provide.

- Cosource or outsource, but stay in control—If IAF competencies are not quite satisfactory, co- or outsourcing can be helpful to achieve benchmarks. In the case of cosourcing, internal auditors should combine the results of various external audits to create an overall opinion and stay on top of reporting, because only they know whether cybersecurity risk management is integrated with enterprise risk management or is an isolated endeavor.

- Engage in all three audit phases—There should be a strong correlation among all three phases of the audit in terms of how thoroughly they are performed. A lack of good planning has severe implications for the performing-the-engagement and reporting phases. Understandably, an audit of a large number of controls will be spread out over multiple years, but the most pertinent risk factors should be identified and prioritized to provide a comprehensive picture of the effectiveness of cybersecurity risk management in the year of reporting.

- Cooperate with the first and second lines—Even though an independent internal audit is important, it should not be isolated from the other two lines, as suggested by the new three-line IIA model.12 Research has found that cooperation among the three lines has very positive results on the effectiveness of cybersecurity risk management.13 Only 8 percent of respondents indicated that they cooperate intensively with the first and second lines in determining risk and dividing assurance activities. Forty-two percent of respondents do not have an assurance plan, and 17 percent do not cooperate at all with the first and second lines. Using assurance mapping to delineate the duties of each line contributes to more efficient use of limited internal audit and IT department resources. Assurance mapping helps formalize in- depth and ongoing cooperation.

Conclusion

Cybersecurity is an ever-increasing priority, and organizations need to be able to measure their cybersecurity audit effectiveness to understand how best to move forward and strengthen their cybersecurity practices. Internal audit is effective if the procedures of planning, performing and reporting on audit findings on cybersecurity risk management follow standards, professional guidelines and best practices.

The results of research show that certifications in IT audit matter but can be partially offset by outsourcing cybersecurity audits to third parties.

The results of research show that certifications in IT audit matter but can be partially offset by outsourcing cybersecurity audits to third parties. Also, internal auditors should be wary of giving the board an overall opinion if the planning and performing stages of internal audit are not done properly. Ultimately, cybersecurity is not just the responsibility of one person or team, it is the responsibility of the entire organization, since collaboration between internal auditors and other teams (e.g., operational IT, information security) leads to better cybersecurity risk management.

Endnotes

1 Sharton, B. R.; “Will Coronavirus Lead to More Cyber Attacks?” Harvard Business Review, 16 March 2020, http://hbr.org/2020/03/will-coronavirus-lead-to-more-cyber-attacks?autocomplete=true

2 European Confederation of Institutes of Internal Auditing (ECIIA), 2022 Risk in Focus: Hot Topics for Internal Auditors, Brussels, 2022, http://www.eciia.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/FINAL-Risk-in-Focus-2022-V11.pdf

3 The Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA), OnRisk 2022: A Guide to Understanding, Aligning, and Optimizing Risk, USA, 2022, http://theiia.mkt5790.com/OnRisk2022/?webSyncID=201dc9eb-b435-9048-2cb7-ea0e42c9b620&sessionGUID=3abc53b6-5e13-0534-1bde-ab510202bd42

4 World Economic Forum (WEF), The Global Risks Report 2021, 16th Edition, Switzerland, 2021, http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_The_Global_Risks_Report_2021.pdf

5 Slapničar S.; T. Vuko; M. Čular; M. Drašček; “Effectiveness of Cybersecurity Audit,” International Journal of Accounting Information Systems, 15 January 2022, http://doi.org/10.1016/j.accinf.2021.100548

6 Agrawal, T.; “Nine Mistakes That Internal Auditors Make,” The IIA Netherlands, 16 January 2017, http://www.iia.nl/actualiteit/nieuws/9-mistakes-that-internal-auditors-make

7 The Institute of Internal Auditors has updated the three lines of defense model and renamed it the three lines model.

8 Op cit Slapničar et al.

9 Association of Healthcare Internal Auditors (AHIA) and Deloitte, “Cyber Assurance: How Internal Audit, Compliance and Information Technology Can Fight the Good Fight Together,” USA, http://ahia.org/assets/Uploads/pdfUpload/WhitePapers/CyberAssuranceWhitePaper.pdf

10 Mutune, G.; “Twenty-Seven Top Cybersecurity Tools for 2020,” Cyber Experts, 31 December 2021, http://cyberexperts.com/cybersecurity-tools/

11 The Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA), “Implementation Guidance,” http://www.theiia.org/en/standards/what-are-the-standards/recommended-guidance/implementation-guidance/

12 The Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA), The IIA’s Three Lines Model: An Update of the Three Lines of Defense, July 2020, http://www.theiia.org/globalassets/documents/resources/the-iias-three-lines-model-an-update-of-the-three-lines-of-defense-july-2020/three-lines-model-updated.pdf

13 Steinbart, P. J.; R. L. Raschke; G. Gal; W. N. Dilla; “The Influence of a Good Relationship Between the Internal Audit and Information Security Functions on Information Security Outcomes,” Accounting, Organizations and Society, vol. 71, p. 15–29, November 2018, http://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2018.04.005

MATEJ DRAŠČEK | PH.D., CSX-F, CFSA, CIA, CRMA

Is a chief audit executive for a regional retail bank in Slovenia. In addition to having served as a lecturer for several universities and faculties, he has published numerous professional and scientific articles on internal audit, human resources, business ethics and strategic management internationally. Drašček has spoken at numerous domestic and international conferences, presenting new tools and insights in internal audit, strategic management and ethics. He won The Institute of Internal Auditors’ (IIA’s) William S. Smith Award for the highest score on the Certified Internal Auditor (CIA) exam and The IIA’s John B. Thurston Award for the best article about business ethics. He is the president of The IIA Slovenia.

SERGEJA SLAPNIČAR

Is an associate professor of accounting at the University of Queensland’s Business School (Brisbane, Australia). She researches the effects of accountability, performance measurement and incentivizing on various employee and organizational outcomes. Her research has been published in top accounting journals. She has extensive board experience through her service as a nonexecutive director for various public organizations. She has worked extensively with the Slovenian Directors Association and has trained more than 1,000 nonexecutive directors in accounting and finance.

TINA VUKO

Is a professor in the department of accounting and auditing at the Faculty of Economics, Business and Tourism at the University of Split (Split, Croatia). Her research primarily investigates the role of internal and external auditing in enterprise governance, financial reporting quality and related regulatory environment. She has published more than 30 research papers and participated in a significant number of academic and professional conferences. She is an active member of the European Accounting Association (EAA) and Croatian Association of Accountants and Financial Professionals.

MARKO ČULAR

Is an assistant professor in accounting and auditing at the Faculty of Economics, Business and Tourism at the University of Split (Split, Croatia). He researches cooperation between internal and external audit, effectiveness of audit committees, application of International Financial Reporting Standard (IFRS) 9: financial instruments, and annual report disclosure quality. He is an active lecturer at several international professional workshops in the field of accounting and auditing, the leader of several professional projects, and a member of the supervisory board of a utility enterprise. He is a member of The Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA), the European Confederation of Institutes of Internal Auditing (ECIIA) and the European Accounting Association (EAA).